Guarda la versione completa su YouTube: NEWSf1IT

The first on-track appearances of the F1 2026 cars have already highlighted one of the most fascinating technical challenges introduced by the new regulations: active aerodynamics.

As discussed in episode 137 of Race Tech on NewsF1.it, attention quickly shifted to how teams manage Low Drag mode at the front of the car, where two clearly distinct design philosophies have emerged.

Watch the full technical analysis on YouTube

(YouTube embed – https://www.youtube.com/embed/ID_VIDEO)

Active aerodynamics in F1 2026: a new technical landscape

The 2026 technical regulations define two mandatory aerodynamic configurations: High Downforce, mainly used in corners, and Low Drag, activated on straights to reduce aerodynamic resistance.

At the front of the car, Low Drag mode is achieved by reducing the angle of attack of the wing elements, lowering drag while maintaining acceptable aerodynamic balance.

Early images from Ferrari, Mercedes and Aston Martin, however, revealed a significant conceptual divergence in how this system has been implemented.

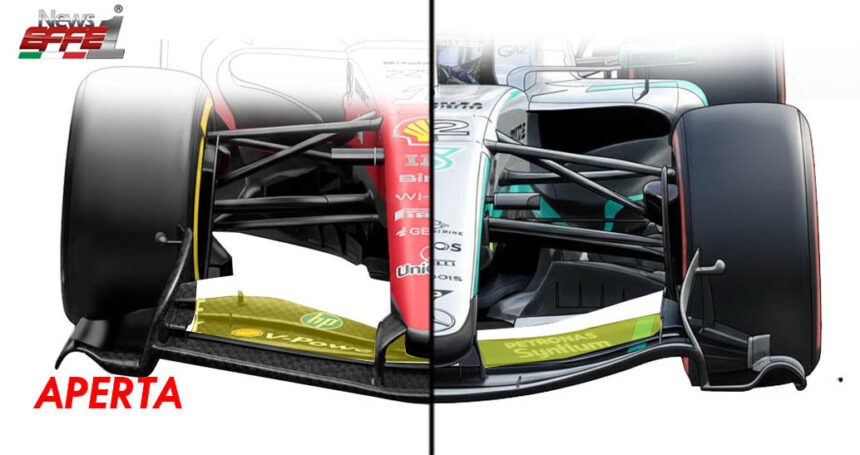

Three movable elements versus two: Ferrari compared to Mercedes

- Ferrari and most teams reduce drag by lowering both the first and second movable flaps of the front wing when switching to Low Drag mode.

- Mercedes and Aston Martin, by contrast, actuate only the rearmost element, keeping the rest of the wing structure essentially fixed.

This is not a marginal detail, but the direct consequence of a specific structural and aerodynamic philosophy.

Mercedes and Aston Martin’s concept: structure dictates function

According to the analysis of engineer Riccardo Romanelli, Mercedes and Aston Martin share a similar approach in how the front wing is connected to the nose.

“The wing pylons do not only support the main element,” Romanelli explains, “they also structurally incorporate the first flap.”

As a result, the main element and the first flap form a single rigid assembly. From a mechanical standpoint, this prevents those elements from being actuated independently.

Consequently, the only surface that can effectively move in Low Drag mode is the rearmost flap, located close to the trailing edge of the wing.

Aerodynamic efficiency: load distribution over surface area

At first glance, limiting actuation to a single flap may appear restrictive. In reality, aerodynamic efficiency depends less on the number of movable elements and more on how much load each element generates.

Mercedes and Aston Martin may have designed a front wing in which the rearmost flap alone produces a substantial portion of the total downforce. Flattening that single element can therefore yield a large percentage reduction in drag — in some respects comparable to the effect of rear-wing DRS.

“It’s a radical solution,” Romanelli adds. “Ferrari works on a broader surface, adjusting the overall angle of attack. Mercedes and Aston Martin focus everything on the trailing edge. That points to very different efficiency targets in the front-wing design.”

Airflow management and aerodynamic balance

The main element remains the aerodynamic reference of the front wing, as it is closest to the ground and plays a key role in directing airflow toward the floor, sidepods and diffuser.

Choosing whether to actuate one or two flaps fundamentally changes how the airflow is conditioned upstream of the underbody. This has direct consequences for overall car balance, especially during transitions between Low Drag and High Downforce modes.

Final analysis

Mercedes and Aston Martin have adopted a more structurally constrained but potentially very efficient front-wing concept for 2026. The real test will be whether this approach can maintain aerodynamic stability when switching back to maximum downforce configuration.